I’m building my online courses for the fall. The fall of 2020. The one wherein we’re still in the midst of the pandemic. I have all these aspirations for my online pedagogy: open pedagogy, OER pedagogy, pedagogy that empowers students to learn how to make online content, pedagogy that inspires students to become readers and writers. And then there’s the fact of the pandemic. I can barely read anything longer than a tweet. I can barely concentrate on anything for more than three minutes. I have a baby. Nearly my entire family just recovered from COVID19. Two of my friends’ parents just died on ventilators.

This is all to say: I can barely put together a regular-degular-schmegular Blackboard site for my students. How am I going to expect students to be more functional than I am? Can I design a course that helps students meet the learning objectives of the courses while accommodating the stress of living in the midst of a pandemic?

I have spent a couple years operating under a philosophy that quantity could lead to quality: get students to read and write a lot, then they’d get better at both. I still believe this, but unfortunately, these activities take time. I read this tweet by Marcos Gonsalez last night:

“more reading/more work is better learning” assumes a universal student, one that has enough time & resources in which to dedicate to the work, & one with a body/mind that can process all that material in short spans of time. More work doesn’t mean better quality of learning.

https://twitter.com/MarcosSGonsalez/status/1284939181735780360?s=20

He emphasizes “method” over “content”. Earlier in the thread, he advocates teaching “fewer texts, carefully selected, paying closer attention to what those texts are doing is more generative for students’ learning & time.” Being more deliberate about the method involves “care,” as he states here. That care takes almost more time than just assigning an entire chapter or article or book does. It means that the instructor has to find the specific bit that generates appropriate student experience.

In mulling over this problem of quality over quantity for the coming semester, culling many of the texts and deliberating deployment, I feel sad. In part because I’m asking myself “Did I make students do a lot of unnecessary work all these years?” (yes). Also because I’m realizing how many of my pedagogical decisions are guided by my ego rather than my consideration of student needs. When I’m planning my courses, I’m always considering what other instructors would think when they look at my materials rather than what students are going to think when they look at them.

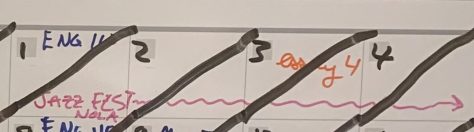

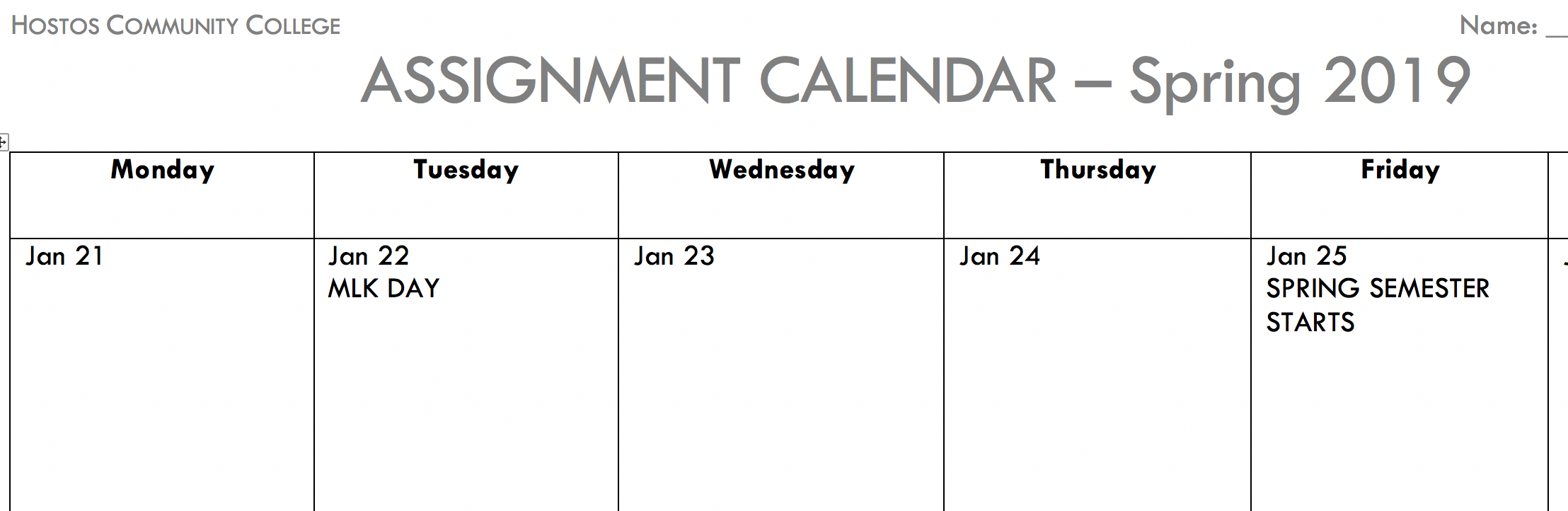

Being self-conscious of one’s syllabi and teaching decisions is baked into the cake: we have to submit the syllabi to administrators. They’re evaluated by committees when we’re being promoted. We have to design them for bureaucracy rather than students’ eyes. For instance, how many students spend a great deal of time poring over our learning objectives or boiler-plate course descriptions anyway? I know that I never did much of that – I’d scramble through looking for the number of essays required and the books being taught. I’m also in a position where I collect and glance over faculty syllabi for a particular course every semester to make sure components are not missing and that grading requirements are being followed. The very things students don’t look at are the things I have to assess when I do this.

The issue of “two syllabi”—one for students, one for administration—irks me before the beginning of each semester. This brings me back to the issue I began with: the issue of designing a course on Blackboard versus building one that I would be really proud of. I’m going to fall back on the former this fall because we are still in “emergency mode”. A colleague of mine made a compelling case for this, saying that students already have to learn to use Blackboard for all their courses, and that it’s unfair to force them to learn whole other platforms in addition in times like these. I will reduce reading expectations and make the site as accessible as possible, but maybe along the way I will build a foundation for a more innovative course for the future.